Foster management professor is developing a novel test for COVID-19 on the side

There is still much we don’t fully know about the enigmatic coronavirus that has wrought havoc around the world. How contagious is it? How deadly? How does it transmit? What is the complete set of symptoms? Why is it so capricious? Does infection confer immunity?

We know one thing for sure, though: there’s not nearly enough testing. Especially in the United States, which has a third of the world’s confirmed cases of COVID-19

Amid a worldwide race to ramp up testing capacity, an assistant professor of management and organization at the UW Foster School of Business (of all people) is working on a solution as novel as the virus itself.

When he’s not teaching and studying entrepreneurship at Foster, Dan Olson runs a biotech company called Exhalent Diagnostics. The startup he co-founded is using nanotechnology and artificial intelligence to develop an inexpensive screening device that can detect disease biomarkers in your breath and produce results in minutes.

This technology was initially designed as a field test for tuberculosis. But when COVID-19 cases began spreading in January, Olson and co-founder Blain Chappell quickly began recalibrating the diagnostic platform to detect the coronavirus that causes infection. It promises to be quicker, cheaper, more accurate and less invasive than existing methods.

There’s just one hitch. A massive bottleneck in demand for labs equipped to work with the novel coronavirus has so far prevented Olson from confirming the efficacy of his company’s diagnostic test.

“It’s hard to convince labs right now to make time for a tiny little startup,” he says. “Even though our test could change the world.”

How things work

If it seems surprising that a management professor would be delving into the world of medical diagnostics, you should know a bit more about Olson.

“I like to know how things work,” he says. “That’s always been interesting to me.”

He started as a math major at BYU before realizing that he was more interested in understanding the underlying principles than in solving equations. So, he switched to philosophy, focusing on logic and the foundations of mathematics.

Finding that a philosophy degree presented limited career opportunities, he enrolled in Harvard Law School to learn how the legal system works. “As a philosophy major, I was used to arguing. And I went to law school thinking I was going to like to argue,” Olson says. “But it turns out that I didn’t really like litigation.”

He loved business law, however, especially as it relates to the art of the deal. In many years practicing transactional law—advising mergers and acquisitions—he became fascinated by entrepreneurs and puzzled at their tendency to follow gut instinct over market intelligence.

When he pursued doctoral studies at the University of Maryland, entrepreneurial decision-making was the natural area of inquiry for him.

Olson’s own entrepreneurial career is the product of serendipity. About the time he was starting his academic career at the Foster School in 2018, he did some consulting for a breath-based diagnostic technology developed at the University of Utah. When it became clear that the inventors weren’t inclined to pursue commercialization, Olson and Chappell, a materials science engineer, convinced the school’s tech transfer office that they could bring the concept to market.

Olson’s own entrepreneurial career is the product of serendipity. About the time he was starting his academic career at the Foster School in 2018, he did some consulting for a breath-based diagnostic technology developed at the University of Utah. When it became clear that the inventors weren’t inclined to pursue commercialization, Olson and Chappell, a materials science engineer, convinced the school’s tech transfer office that they could bring the concept to market.

They licensed the technology and launched Exhalent Diagnostics to do just that.

Blow in the bag

The two most prevalent existing methods of COVID-19 testing have significant limitations. The “nasal swab” PCR diagnostic is inaccurate during early stages of an infection, and most versions must be sent to a lab to process. The antibody blood test detects past coronavirus infection, but it is not useful as a diagnostic for current cases. And neither is available in anything close to the volume that public health experts believe will be required to open the economy while keeping the virus in check until a vaccine is developed.

Olson believes Exhalent’s emergent sensor technology can do better.

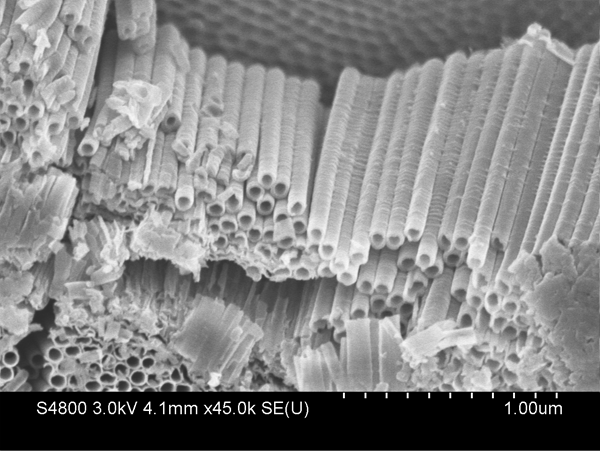

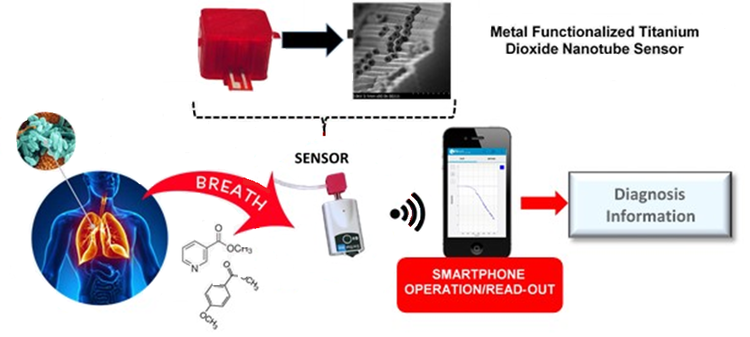

It is made of self-organizing titanium dioxide nanotube arrays that can be structured to precisely detect specific molecules, including biomarkers associated with a variety of diseases (as well as the active ingredients in illegal drugs).

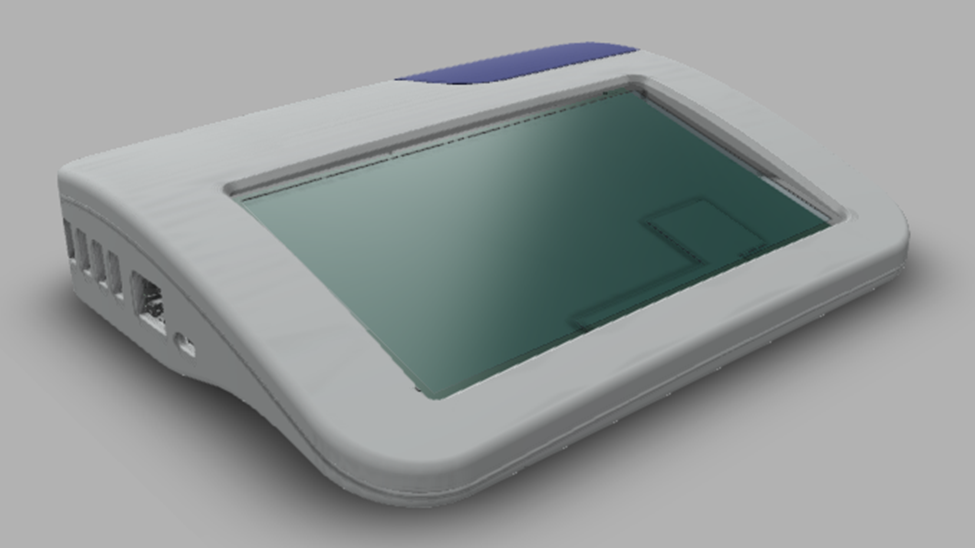

This sensor is housed inside a tablet-sized device with an external port that accepts a disposable bag with two valves. To get tested, you blow into the bag’s open valve and a pump passes the exhaled breath into the device and across the titanium dioxide sensor. When target molecules are present, they interact with the nanotubes and create a measurable electrical response which is interpreted by a trained algorithm and communicated to a tablet or smartphone in minutes.

The device was designed for tuberculosis field testing in India and Africa, so it is portable and rugged and simple to operate. And it’s comparatively cheap: $10 per test is the estimated cost, though Olson says it could be administered at an even lower price in an emergency.

“We were building a test priced to work in the developing world,” he says. “But it doesn’t cost any more to run it here. And we would much rather make it accessible to test everybody.”

Trying to test the test

Exhalent Diagnostics was on track to field test its tuberculosis diagnostic, through the World Health Organization, early this year—until the novel coronavirus moved TB to the back burner.

Had initial testing been even a few months further along, Olson believes the proof-of-concept would have opened doors to fast-track evaluation of the breath-based sensor for coronavirus.

The Exhalent Diagnostics point-of-care screening prototype is built to be portable and rugged enough for field testing.

As it stands, his nano-sized company is still looking for a few hours in a BSL-3 lab to confirm that its diagnostic technology can be calibrated to conclusively detect the SARS CoV-2 virus (which causes COVID-19). There are only a few hundred of these labs scattered across the nation—and most are beyond capacity processing existing COVID-19 tests and investigating potential therapies and vaccines.

“The frustrating thing is that I can’t point to an inefficiency,” Olson says. “The labs where we would do this kind of scientific experiment are the same ones that are actually processing the current tests.”

Next steps

Exhalent Diagnostics has plenty of avenues to commercialize its breath-based biomarker screening technology. Preliminary indications of its ability to detect the active ingredient in methamphetamine and other illegal drugs has the attention of law enforcement. There are plans to test its ability to spot-diagnose E.coli contamination in a dairy processing plant. And Olson and Chappell intend to pursue other potential applications in testing for various cancers, pneumonia and a litany of infectious diseases.

Plus, they still plan to execute on the findings of several published academic papers and a field study that show the sensor successfully detects unique biomarkers of tuberculosis, which infects 10 million people—and kills 15 percent of them—each year.

“We see so many different applications for a sensor that can pick up volatile organic chemicals in our breath,” Olson says. “With what is essentially a software update, the same device can be used to detect all kinds of things.”

For now, though, Olson is channeling most of his entrepreneurial energy into testing the virus that has sent 7.8 billion people into hiding. Even if it takes a while longer to confirm efficacy, pass regulations and ramp up manufacturing of the device for COVID-19 screening, it could still make a big difference.

For now, though, Olson is channeling most of his entrepreneurial energy into testing the virus that has sent 7.8 billion people into hiding. Even if it takes a while longer to confirm efficacy, pass regulations and ramp up manufacturing of the device for COVID-19 screening, it could still make a big difference.

“If this is going to be a cyclical virus, as many predict, our diagnostic may be useful for a while to come,” he says.

Especially as we venture back to work, to school, to leisure, to travel—together.

“I certainly don’t want to make any guarantees,” Olson says. “But we know that this technology works for other diseases, and it doesn’t cost a whole lot. We may have a solution.”

A lesson for the teacher

Whatever happens with Exhalent Diagnostics, Dan Olson says that the experience has been invaluable to his academic career.

“It’s been insightful to go through the process that I know my entrepreneurship students will go through, and to feel the emotions they feel,” he says. “Plus, I now have a reality check for the theories that I study and teach.”