Northwest Classic

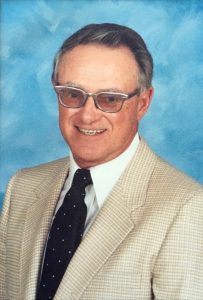

Elton Leith, an “everyday guy” with an extraordinary gift, lived an entrepreneurial life in parallel with the Foster School of Business

When he was 14 years old, Elton Leith (BA 1942) traveled to Snoqualmie Pass with his Boy Scout troop to learn how to downhill ski. He noticed some of the experts scything effortlessly down the slopes with the aid of two slender poles.

When he was 14 years old, Elton Leith (BA 1942) traveled to Snoqualmie Pass with his Boy Scout troop to learn how to downhill ski. He noticed some of the experts scything effortlessly down the slopes with the aid of two slender poles.

At the time, twin-pole skiing was still a recent innovation to the ancient sport. And strong, lightweight ski poles made of imported bamboo were hard to come by—especially for a hardscrabble kid from Seattle in the depths of the Great Depression.

But young Elton got a twinkle in his eye.

“I could make those,” he thought.

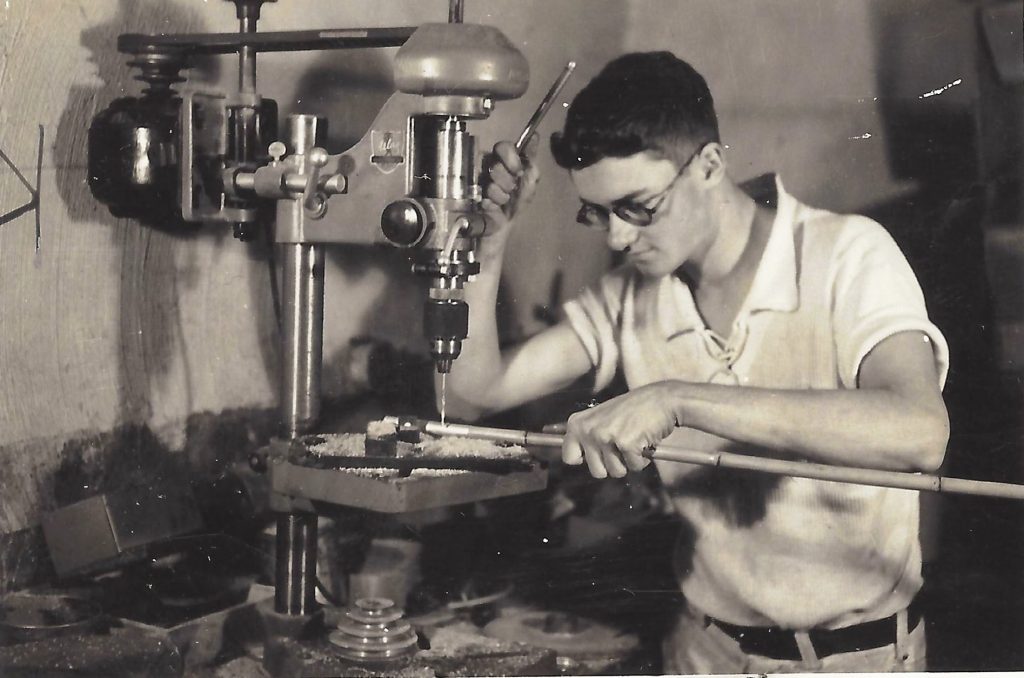

And so he did. First for himself and his friends. Then, in short order, for the paying masses. The enterprising young man ran his Cascade Outing Supply Company out of his family’s basement. He imported Tonkin cane, a straight, smooth, thick-walled bamboo, from Thailand, and fashioned the baskets out of Singaporean rattan and leather from Oregon. He sold thousands of pairs of custom-made poles and eight kinds of ski wax to customers from Seattle to San Francisco to New York City.

Elton’s cottage industry helped the family through some lean years, and even financed his education at the University of Washington where he, unsurprisingly, studied business.

“Dad was a real entrepreneur,” says Elton’s daughter Lorin, “before anyone had ever heard of the word.”

But entrepreneur only begins to tell the story of this quintessential son of the Pacific Northwest.

Vintage Seattle

Robert Elton Leith was born at Seattle’s Swedish Hospital in 1917, the same year as the UW Foster School of Business.

He was hewn of rugged stock, the descendent of coal miners from England, gold rush traders from the Scottish Isles of Orkney, and pioneers of the Oregon Territory.

The only child of Mildred and Robert Leith, a former logger who worked as an engineer for City Light, Elton grew up in the Rainier Valley with his trusty dog, Rip. The Seattle of his youth was the rough-and-tumble town depicted in The Boys in the Boat, Daniel James Brown’s bestselling account of the underdog Husky rowing eight that won gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympiad. In fact, Elton knew a few of those legendary oarsmen personally.

As a kid, he picked fruit in the neighborhood orchards and delivered newspapers to make a buck, dodging the menacing bootleggers’ dogs that roamed his tough South Seattle neighborhood. A ruptured appendix, before the days of antibiotics, nearly killed him. A long bout of pneumonia delayed his graduation from Franklin High School.

But Elton was resilient. And he loved the sanctuary of the great wilderness beyond the city borders. His family spent many happy summer weeks hunting the forests, fishing the lakes, clamming the beaches and hiking the mountains of the Olympic Peninsula, often from a base camp on the shores of Lake Ozette. “We didn’t have any money,” he recalled, “and it was a cheap way to have a holiday.”

Cascade outing

Elton’s ski equipment business, though, grew like “a snowball rolling downhill,” according to an article on the DIY teen entrepreneur in the Seattle Star.

He sold his wares via local outfitters Eddie Bauer, Warshall’s and Seattle Sporting Goods. When an Olympic ski coach from an Ivy League school saw his state-of-the-art poles while training on Mount Rainier, he convinced an East Coast retailer to carry them.

To keep up with demand, Elton employed neighborhood friends and his family. “His grades go down during ski season,” his mother admitted to the Star.

But Elton’s basement enterprise was a means to an end. He wanted a college education.

His illness-plagued adolescence delayed his start at the UW School of Business Administration. And managing the business meant an extended stay. It didn’t do wonders for his GPA, either. “I was always working too much to spend as much time as I would have liked on my studies,” he recalled.

But Elton made it through, with the help of the legendary Donald Mackenzie, a favorite professor of shared Scottish heritage who would invariably greet his student with a hearty “Hello… Leith!”

At the UW he earned his business degree and fell in love with Mildred Wright, a nursing student who would soon become his wife.

War effort

Elton graduated in 1942, shortly after America entered World War II. He volunteered to serve, but was denied for his terrible vision (he could see only through glasses with Coke-bottle lenses), flat feet and a positive test for tuberculosis.

Nevertheless, he was determined to contribute to the war effort. After graduation, the Leiths moved to Portland where Elton put his business degree to work supervising at the Kaiser naval shipyards while Mildred took a job in Vanport, the hastily constructed settlement on an ill-fated bend of the Columbia River—later destroyed by flood—to house the influx of shipyard workers from around the country.

After the war, the couple returned to Seattle. Lorin was born in 1949. And Elton decided it was time to become his own boss once more.

Ski poles had gotten him through college. His family’s future would be in laundry.

Clean living

Resettled in Seattle, Elton purchased a single coin-operated laundromat, then acquired a small washer service company from its retiring founder. He methodically built a regional empire of coin-op machines for renters and appliance sales and service for home owners.

It wasn’t a flashy business. But it was very profitable. Elton had foreseen the post-war boom, and knew how to take advantage of a market opportunity. His fair and generous demeanor forged a fiercely loyal team of customers and employees, among them a number of women promoted to key management positions.

By his 50s, Elton had earned enough from the business to retire comfortably. He took care of Mildred, who had advancing multiple sclerosis, until her death in 1983. He eventually remarried, to Barbara Wescott Sievers, and split time between Whidbey Island and Palm Desert before moving to Santa Rosa, California, to be near his daughter.

Elton became an avid golfer in his retirement, a fitting pastime for a man with the surname of Leith that is shared with the famous links course near Edinburgh where the game’s earliest rules were recorded.

He also became increasingly invested in giving back for his good fortune in a life that extended longer than he could have imagined. He financed student support at Santa Rosa Junior College, where his daughter taught ESL to first-generation immigrants, and at the UW. And his bequest of $1 million to the UW will leave a legacy of endowed scholarship support to students in perpetuity.

Elton didn’t often talk about the reasons for his philanthropy. But Lorin knew. “Because he was such a poor kid who really worked hard to get through school, Dad felt like giving a hand up to others,” she said. “I think he’s been impressed with these kids who come to school with nothing, work extremely hard and, with so much against them, accomplish so much.”

The good life

We became acquainted with Elton in early spring of his 100th year, at the end of a life that paralleled the school that educated him. He was in hospice care at the time, and Lorin was instrumental in helping us chronicle his story.

When informed that he was—according to alumni records—likely the oldest living alumnus of the Foster School and that we were going to write an article on him, he was surprised, even tickled. “He saw himself as your everyday guy,” Lorin reported.

Well, not every everyday guy wills $1 million to his alma mater.

Elton Leith died last March, a few months shy of his 100th birthday. “He related to people, took care of people,” Lorin said. “He was funny and kind, hardworking and unpretentious, blunt and outspoken—people loved even that about him.”

In his final days, Elton recalled his youth with astounding clarity. His time at the UW, his basement ski pole business, the neighborhood dogs, the family camping trips.

The best old days of his many years played over in his mind. The farther away, it seems, the more crystalline the memories.

Shortly before he passed away, Elton dreamed of duck hunting with his dad.