Oscar-winning American Factory and the challenges of cross-cultural workplaces

Looking for a little management education to go with your diversionary entertainment as you practice social distancing and shelter in place amid the COVID-19 pandemic?

You might consider streaming American Factory, winner of this year’s Academy Award for best documentary, on Netflix. American Factory is an immersive and intimate account of the culture clash that arose when Fuyao, a Chinese automotive glass maker opened a manufacturing facility in a shuttered General Motors plant in Dayton, Ohio.

It also unfolds as an instructive case study in the challenges facing cross-cultural organizations.

To unpack the film’s trove of management insights, we asked for some expert perspective from Xiao-Ping Chen, a professor of management and the Philip M. Condit Endowed Chair in Business Administration at the UW Foster School of Business. Chen is a native of China who has spent most of her professional career in the United States. She’s recently written a book on successful Chinese entrepreneurs and is an authority on cross-cultural workplaces.

Were you excited to see a film take on a topic so near to one of your areas of research?

Yes! I watched it with great interest. It reminded me of an earlier movie by Ron Howard called Gung Ho (the 1986 comedy, starring Michael Keaton, that found humor in the takeover of an American car plant by a Japanese corporation). Gung Ho was more dramatic and a lot funnier, though.

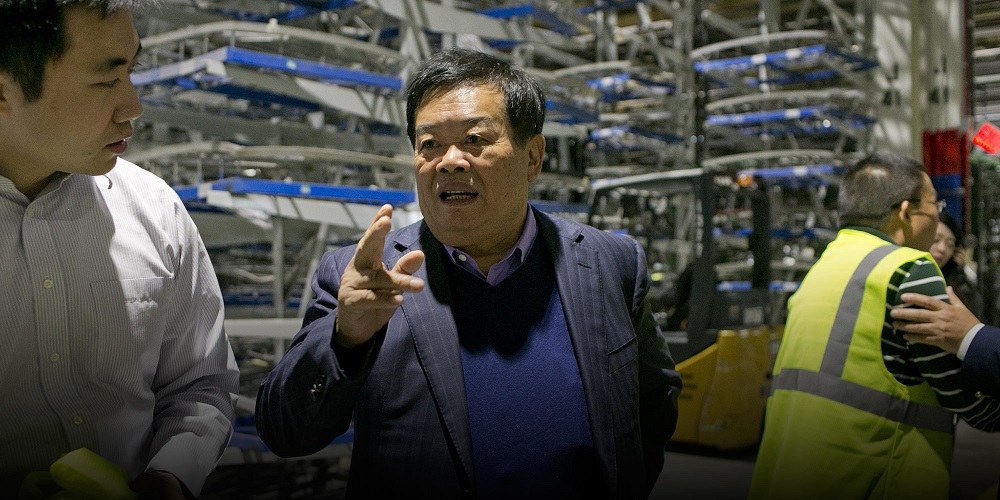

American Factory spent time with Fuyao’s American workers, the Chinese expats brought over to manage them, and even Cao Dewang, the company’s billionaire founder and chairman. Fascinating character, yes?

Chairman Cao is very famous in China. He has built his own private enterprise and is a good example of an old-school patriarch-leader—very different style than a more modern Chinese leader like Jack Ma (of Alibaba). When Cao announced he was going to open a factory in the United States, he faced a lot of backlash from the Chinese people for moving manufacturing jobs to the US. But he said, we’re not going there to make quick money. We want to establish a new image about China through this collaboration. So every Chinese manager brought over, to some extent, represents the country.

Chairman Cao goes to great lengths to dissuade Fuyao America employees from joining a labor union. Can you contrast this from the encouragement of Fuyao’s Chinese workers to take part in their local union?

In the chairman’s mind, American-style unions are a barrier to efficiency and productivity, which is really not so different from the stance of some U.S. companies. In China, every company has a union. But they play a totally different function. Instead of pitching against the management, they support the company by offering social events such as Chinese new year celebration (as seen in the documentary) and helping employees to solve problems related to personal life such as dating, wedding, or child care. This derives from the traditional dynamic of the CEO as father figure to a family of employees.

The Chinese and Americans at the plant seem to have a different relationship to work. Is there a significant cultural difference?

There are different norms and expectations in the way organizations relate to their employees and employees relate to their organizations. In cross-cultural research, career success versus quality of life is one of the value orientations we compare. In the U.S., many people see them as being separate: career success is important but after-work hours and weekends are mine. Chinese people believe these two are highly connected: if I don’t achieve success at work, I can’t have a higher quality of life. So, especially when I’m young, I should focus on career success and work really hard. More people in China live to work than work to live. Work is very important.

What are some other common sources of culture clash observed in the documentary?

What are some other common sources of culture clash observed in the documentary?

Compared to the U.S., China generally has a much higher power distance, which is its relative relationship to authority. In China, a CEO is basically a king of his company. At every level of an organization, people give their leaders great respect. We generally don’t see that kind of disciplined hierarchy in the U.S., outside of the military.

Difference in power distance also affects employee voice. People everywhere want better pay and safer working conditions. But where Americans are willing to voice their wants and needs, Chinese people are less likely to complain.

Also, Americans often crave recognition and appreciation; they’ve been brought up being praised. Chinese are more used to being criticized; their ‘tiger moms’ and ‘wolf fathers’ believe being critical makes kids grow faster.

Are these longstanding cultural norms in China changing at all?

Yes, the younger generation, born after 1990, is different. Especially educated young people. The ‘Post-90s’ are products of the one child policy and a growing economy. They don’t care to work all the time. They want their weekends. Their power distance may be shrinking, too. If the boss says, ‘You need to work overtime,’ they don’t care. These young people are used to being the emperors of their families. Maybe the attitudes of young people around the world are converging.

American Factory can feel like a cautionary tale. Can the organizational merging of distinct cultures work?

The challenge is to what extent people can communicate with and understand each other at a deep level. We saw in the documentary that there was one Chinese manager who was able to communicate pretty well with his American colleagues. They seemed to appreciate and respect each other, and communicate in an open and deep rather than superficial way. By the end, they became friends.

As human beings, we share a lot of things in common. If we start from these common values, then it’s much easier to navigate these cultural differences. All human relationships are based on trust. Instead of focusing so much on differences, let’s start with what we have in common, then identify the differences that we need to address.

As human beings, we share a lot of things in common. If we start from these common values, then it’s much easier to navigate these cultural differences. All human relationships are based on trust. Instead of focusing so much on differences, let’s start with what we have in common, then identify the differences that we need to address.