Keep Clam

The ballad of Ivar Haglund, the whimsical, inimitable marketing genius so essential to the history of Seattle and the Foster School of Business

Ivar Haglund (BA 1928), the legendary restaurateur, raconteur and ringleader of Old Seattle, was a man of many gifts.

Ivar Haglund (BA 1928), the legendary restaurateur, raconteur and ringleader of Old Seattle, was a man of many gifts.

An elfin charm. A sweet tenor. A mind for branding. A knack for promotion. An affinity for zany stunts and cornball puns. A devotion to his city and its waterfront. A mischievous spirit. A generous soul.

But Ivar’s greatest gift of all may have been his final one.

After he passed away in 1985, his last will and testament revealed that the vast majority of his estate was to be donated, in equal parts, to Washington State University’s School of Hospitality Business Management and the University of Washington School of Business (now the Foster School).

Once the paperwork had settled, the total bequest to each of the schools came to $5.2 million. A lot of clams.

The scale of this unexpected gift was stunning. It was—by far—the largest the Foster School had ever received. But perhaps most remarkable was that the money arrived without strings or fanfare, accompanied by a humble directive: to be used at the discretion of school leadership.

“It didn’t matter to Ivar if he got credit,” says Bob Donegan, the current president of Ivar’s Inc. “All he wanted was for kids to get a great education.”

The singing entrepreneur

Haglund’s own education—at least the formal kind—culminated at the UW College of Business Administration, where he earned a BA in economics in 1928. “An ironic degree to get a year before the stock market crash of 1929,” noted historian Paul Dorpat, who’s working on Haglund’s biography. “But Ivar was always ahead of the times.”

At the UW, Haglund sang with the Glee Club, and earned side cash performing a song-and-dance routine peppered with bits of comedy.

He passed the Great Depression living the bohemian idyll of a folk-singing troubadour who kept company with the likes of Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie and Burl Ives.

The UW’s 1928 Varsity Glee Club, with Ivar Haglund standing in the second row, second from the left.

But Haglund, the son of Swedish and Norwegian pioneers, had industry in his blood. Plus, an abiding passion for the Seattle waterfront that developed during his long trolley commutes to the UW campus from his family home on Alki Point.

In 1938, Haglund opened one of the city’s first aquariums, on what is now Pier 54. More significantly, he also opened an adjacent fish-and-chips stand to serve hungry patrons.

Soon enough, he realized that there was more money to be made in seafood to eat than to ogle.

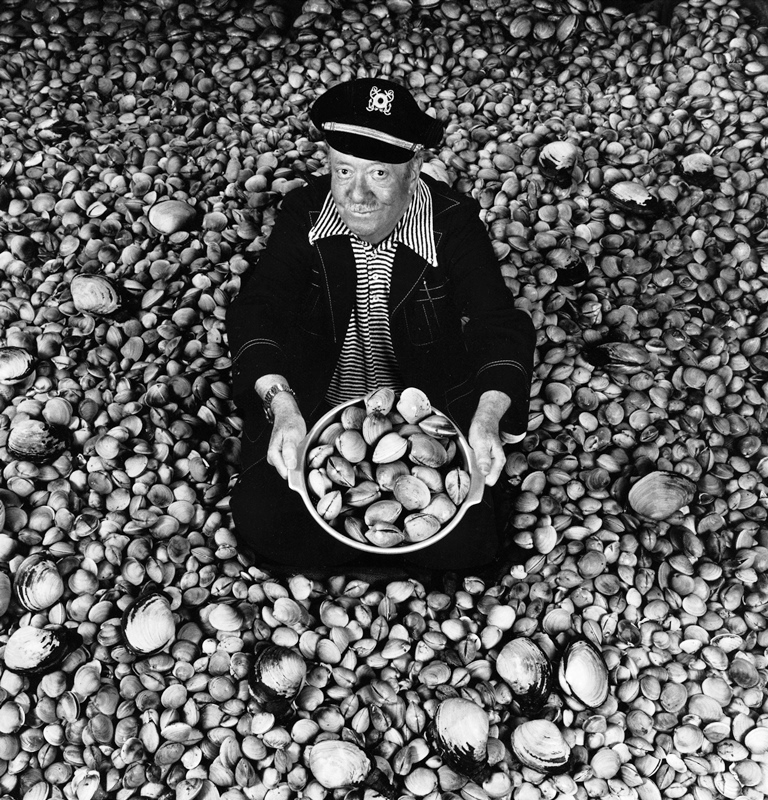

Ivar’s Acres of Clams opened in 1946, a full-service restaurant embellished with kitchsy nautical décor. And a regional empire of eateries grew from there, on a steady diet of fresh local seafood and inventive promotion that was packed to the gills with gut-busting songs, groan-inducing puns, and headline-grabbing stunts—for publicity and, well, just for the halibut.

Stunt man

A career of strategic tomfoolery began in December 1940, when Haglund trundled his aquarium’s star seal, Patsy, in a baby buggy to Frederick & Nelson for the first of many annual visits to Santa Claus.

He regularly convened a cabal of Seattle’s most powerful newspapermen to brainstorm new and fantastic ways of promoting his growing enterprise.

There was the $5,000 reward offered to anyone who could deliver to the aquarium the sea monster that Haglund reported to have spotted swimming in Lake Washington. Then a ballyhooed wrestling match between washed-up prize fighter Tony “Two-Ton” Galento and Oscar the Octopus. And the invention of “Ever-Rejuvenating Clam Nectar” transformed spent cooking liquid into an aphrodisiac of such reputed potency that a third cup was allowed only with the written consent of a man’s better half.

In fact, a daily diet of Ivar’s nectar was claimed to be the key to victory in the first Seattle Clam Bowl, a competitive eating contest mounted by Haglund’s International Pacific Free Style Amateur Clam Eating Contest Association (IPFSACECA). The event garnered world-wide attention.

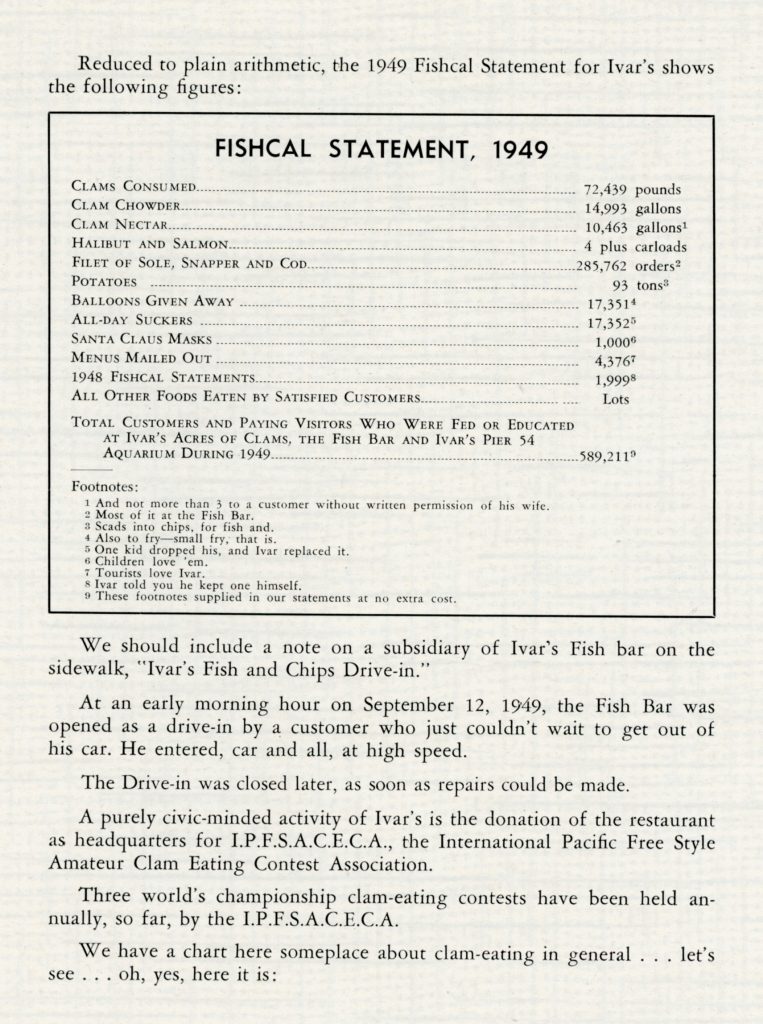

So did the publication of Ivar’s “Fishcal Statement” in the Wall Street Journal, featuring an org chart of menu items, an infographic on the health benefits of seafood and a winking explanation that “there will be no dividends until we have found the key to the petty cash drawer.”

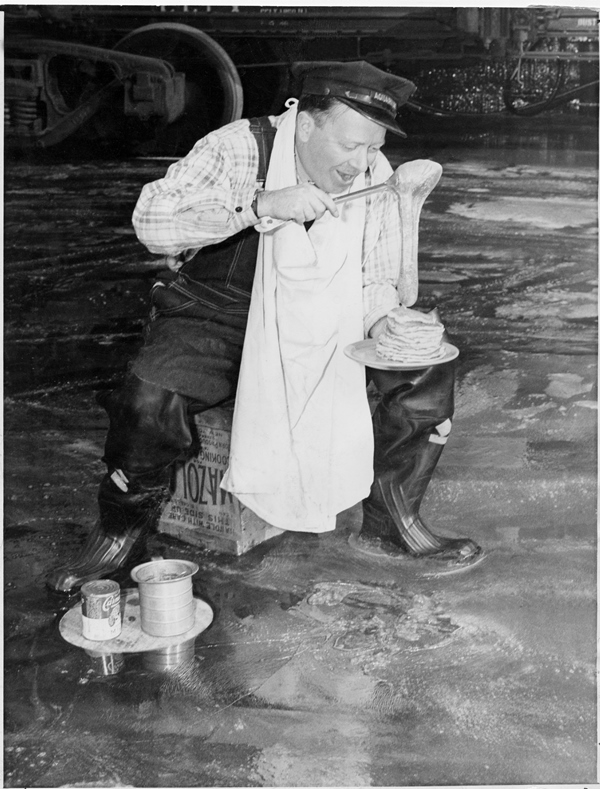

Haglund’s stunts weren’t always planned, either. When a railroad tank-car spilled 1,000 gallons of corn syrup on the train tracks in front of Acres of Clams, he was there in a flash with hip waders and a tall stack of pancakes, ladling on the runaway goop as photographers captured yet another front-page photo.

Marketing genius

Of course, Haglund continued crafting his persona as beloved and benevolent huckster. He never stopped performing on radio and television, singing ballads and chanties that served as subtle—and sometimes shameless—reminders of his nautical enterprise. His most famous went like this:

No longer a slave of ambition

I laugh at the world and its shams

As I think of my happy condition—

Surrounded by acres of clam-m-m-s!

The consummate entertainer was always promoting.

Even Ivar’s signature motto—“Keep Clam!”—was the perfectly eccentric Northwest twist on that famous articulation of the British stiff-upper-lip.

“Ivar was a natural marketer,” says Doug MacLachlan, a professor emeritus of marketing at the Foster School. “He had good instincts and quirky ideas that endeared him to a wide audience and patrons of all ages.”

Look a bit closer and it begins to look like genius.

Haglund certainly entertained the masses as the crooning clown in the captain’s hat. But there was method to his madcap. “It was a rare thing for families to eat out in the ’50s and ’60s,” explains Donegan. “Ivar made it seem fun, not fussy.”

The man behind the legend

Of course, the commercial Ivar was a character, a long-running installation of performance art that provided his beloved city with 1,001 fish tales—as well as a lot of tasty fish.

The real Ivar tended to be quiet, introspective and intensely loyal. He was a shrewd and perceptive business man who saw opportunities that escaped the grasp of others.

He also cared deeply about Seattle, leading countless preservation and improvement initiatives—both formal and freelance. Late in his life he purchased the historic Smith Tower to save it from disrepair. And when he ran for Port commissioner in 1983—largely as another publicity stunt—he won.

What might define Haglund more than anything, however, was his deep sense of empathy. He was quick to connect with people and causes. This inspired a lifetime of philanthropy both small (providing clam chowder to the Millionaire Club Charity) and large (underwriting the annual “4th of Jul-Ivar” fireworks from 1964 until decades after his death).

But nothing approached the scale or scope of his parting gift to the UW and WSU.

Whale of a legacy

An endowment that now pays out more than $600,000 annually to enhance education at the Foster School is only part of Haglund’s enormous legacy.

Ivar’s is stronger than ever today, with 82 restaurants across the Northwest, a concessions business, tankers of chowder sales and upwards of 1,300 employees during its busiest season.

An 80-year-old restaurant company is one of the rarest fish in the sea. Donegan, a whimsical president in his own right, gives credit to Haglund. “Part of the reason we’re still around is that the principles he established still guide us,” he says. “We don’t measure success by profitability first. We measure it in employee satisfaction. Because we know, as he knew, that if our employees are happy, they will make customers happy.”

For Ivar, good food and good fun always went together.

That has always been the Ivar way. And good food and good fun are gifts that, apparently, keep on giving.

A few years ago, divers dredged up several weathered Ivar’s billboards from the bottom of Elliott Bay. They were reported to have been installed by Haglund in the 1950s upon learning of a plan by Washington State Ferries to add fast submarine service from Bainbridge to Seattle. One of the billboards advertised “Ivar’s chowder. Worth surfacing for.”

It was all revealed to be a hoax, of course, a light-hearted conspiracy of Ivar’s leadership, a local ad agency and even the historian Dorpat to create publicity for the company while paying homage to its late, great “flounder.”

“It was very much in the spirit of Ivar Haglund,” explained Dorpat, sheepishly, in the Seattle Times.

Indeed. And, like so many of the memorable stunts and pranks and antics and escapades that Haglund actually did concoct in his life… it worked.

Ivar’s chowder sales quadrupled.

Flexible Funds, Forever

Over the past four decades, the Ivar Haglund Endowment has become the Foster School’s ultimate utility fund, quietly financing innumerable unmet needs and unexpected opportunities.

In the 1990s, fund income seeded the launch of Foster’s student-focused Global Business Center, Consulting and Business Development Center and Buerk Center for Entrepreneurship. It has supported recruitment of traditionally underrepresented students as well as research efforts, career services and instructional computing. It has underwritten an MBA curriculum overhaul, plugged gaps in the operating budget and retired debt on the game-changing PACCAR Hall. It transformed a humble alumni newsletter into a full-blown magazine.

And proceeds from the Haglund Endowment have supported generations of students—many of whom will never know their unnamed benefactor.

And proceeds from the Haglund Endowment have supported generations of students—many of whom will never know their unnamed benefactor.

“In almost all businesses and, certainly, at business schools, there is always some unanticipated need for funds,” says Jim Jiambalvo, the Orin and Janet Smith Endowed Dean at Foster. “In spite of the ups and downs of the economy and state support for higher education, the discretionary dollars provided by the Ivar Haglund Endowment have been vital to the Foster School’s upward trajectory.”

Through many years of responsible stewardship, this deep reservoir of opportunity funding has grown to nearly $15 million today, distributing more than $600,000 annually to help students get a great education.

All of this would please the big-hearted benefactor of this fungible fund to no end, says Frank Madigan, the executor of Haglund’s estate and COO of the 80-year old Seattle seafood company.

“The way that Ivar gave his gift—with no strings attached—was the way he ran his business, too. He gave you authority and then got out of the way,” Madigan says. “He would be thrilled to know how the UW has been using it.”

1 Response

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Wow. Great story. Love it. And love Seattle too. Thankful for stumbling about this on Thanksgiving.