Trip to the American South

Guest Post By: 1st Year MBA Student, Marcel Gremaud. During Spring Break 2022, Marcel traveled to the American South for the University of Washington: Race, Culture, and Business Immersion class.

This spring, 20 Foster MBA students embarked on a personal and professional journey, participating in the inaugural Race, Culture, and Business MBA Immersion program. This program was the work of many hands, starting with Ed deHaan, the Gerhard G. Mueller Endowed Professor in Accounting, recognizing a need to bring tough and important conversations out of the classroom. Professor deHaan reached out to the Global Business Center to see what type of immersive, experiential learning program could be developed to explore the spaces where race, culture, and business intersect. With support from a Foster Purpose Grant, generous donors, and guidance and leadership by local 501(c)3 non-profit, Sankofa Impact, Professor deHaan, and the MBA Program Office’s Norah Fisher, Foster successfully launched the Race, Culture, and Business MBA Immersion to the American South.

This past spring break, 20 MBA students and I took a trip to the American Deep South for the inaugural class of “Race, Culture, and Business.” Led by Sankofa Impact – a nonprofit dedicated to confronting racism through place-based learning experiences – we traveled over a thousand miles by bus from Louisiana to Mississippi to Tennessee to Alabama to Georgia, tracing 400 years of racial history in seven days.

While white senators chastised Judge Ketanji Jackson in confirmation hearings, we listened to Dr. Carolyn McKinstry, a survivor of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, recount how she was sprayed with fire hoses in Birmingham as she marched against segregation.

While Black organizers fought to unionize an Amazon warehouse in Staten Island, we visited Sloss Furnaces, a retired iron making plant in Birmingham that once relied heavily on the labor of wrongly convicted Black men leased by the State.

While politicians around the country declared they would “ban Critical Race Theory in all schools,” we listened to Bob Zellner, the first white Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee field secretary, describe the time KKK members attacked a bus of anti-segregation activists, tore open their suitcases, gathered their books, and piled them up to burn.

The more we traveled, the more places we saw and touched, the thicker the threads between past and present wove together, the smaller the space between then and now became. Some of the stories I thought I knew became more complex, others clearer. This is a snapshot of my experience.

Boarding the Bus to New Orleans

From 1619 to the mid 1800s, six million African people were captured, brought across the Atlantic to America, and sold like cattle. Two million others died along the trans-Atlantic journey. Subjugated to torture, psychological terror, and murder by their enslavers, Africans and their descendants built the foundation of this country, from the wall that Wall Street is named after, to the homes and wealth of presidents like Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson.

The majority of enslaved people worked on plantations like the Whitney Plantation – the only preserved plantation in America today dedicated to telling the story of enslaved people. Plantations were horrific, highly managed human factories, often with regimented operations and modern accounting methods. By brutalizing Black bodies and minds, this system generated immense profits; in the early 1800s, enslaved people in the South were more valuable than all the Southern land combined.

One of the cabins that enslaved people at the Whitney Plantation lived in. 8+ people would be crammed into these two room structures.

But slavery was not simply a Southern problem; a complex financial system that included British banks and Northern corporations fueled its demand. Once the importation of enslaved people was made illegal in 1808, these financial systems continued to allow the domestic slave trade to flourish. In Montgomery, enslaved people were imported by steamboat from the more northern South and forced to walk shackled along Commerce Street to the slave market. There they would be separated from their loved ones and auctioned alongside animals. Nearly half of all enslaved people would be separated from their entire family during slavery.

Commerce Street, the route along which enslaved people were taken into Montgomery

Economic gain was the driver of slavery; racism was the tool. By creating and perpetuating a myth of racial inferiority, whites could justify the mental and physical torture necessary to hold this system together. To exploit the monetary gains of slavery, white people had to believe Black people could not feel pain, that they were less than human, that they could not love their children. These beliefs were codified into laws that made Black people property, prohibited marriage between whites and Blacks, disavowed learning to read, allowed for the “cutting off of ears” of runaway enslaved people, and numerous other horrific rules. Racism outlasted the chattel slavery it was created to enforce, morphing into new laws and beliefs that continue to this day.

Though slavery was decreed illegal during the Civil war, for many it simply took on a new form. Barred from owning land in most southern states, millions of formerly enslaved people were kept in debt peonage as sharecroppers, working until their death the exact lands they had while enslaved by law.

Insidious new laws sprung up in places like Alabama, which made it illegal for Black people to not have a job, to “loiter”, or do any number of petty things. These laws exploited a loophole in the 13th Amendment that prohibited slavery except as a punishment for crime. Hundreds of thousands of free Black people were arrested and then leased out to corporations. Owned and controlled by private companies, wrongfully convicted Black men and women died at a rate 10x the national average. The economic gains from this arrangement were enormous; in the late 1800s, the convict leasing system generated over 70% of Alabama’s state revenue.

Sloss Furnaces: a massive factory that once produced hundreds of thousands of pounds of iron annually, powered in-part by legally enslaved Black workers.

Unwritten rules were reinforced by white communities through racial terrorism. For more than 80 years after the Civil War, whites attempted to control Black people through brutal lynchings. Lynchings were horrific public murders, attended by sometimes thousands of people. Pieces of the victim’s body were often cut off and taken as souvenirs. Justifications for these murders ranged from “looking at a white woman wrong” to “protesting the lynching of a son”. The generational trauma of these murders and their unwritten rules cannot be understated; a parishioner at 1st Baptist Church in Montgomery told me, “ it took me 70 years to be able to hug a white woman at our church without being terrified.”

My classmate Jay examines the plaques at the Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery Alabama, the only memorial dedicated to honoring the 4000+ victims of racial lynchings.

Racism continued its pernicious mutation into the 20th century. Segregation demeaned and humiliated Black citizens while exacerbating economic and healthcare disparities. Dr. Carolyn McKinstry, an activist in Birmingham and the victim of a racial terror bombing that killed four of her friends, recalled to us, “I watched my grandmother die in a basement because a white hospital would not take her.” Redlining prevented Black people from accessing capital to invest in businesses and homes. Jim Crow laws such as literacy tests and poll taxes prevented Black people from voting. Interracial marriage was illegal in many states up until 1967.

Many of us have seen the symbols of segregation in our middle school textbooks: “whites only” drinking fountains, a young Black child being screamed at by a white woman as she walks to her first day of class at Little Rock high school. These black and white photos can easily lull us into believing that the Civil Rights Movement was long ago. But having met some of the Civil Rights foot-soldiers, people who fought alongside the likes of Dr. MLK Jr. and Rosa Parks, this couldn’t be further from the truth. They are still very much still alive, still processing, and still fighting.

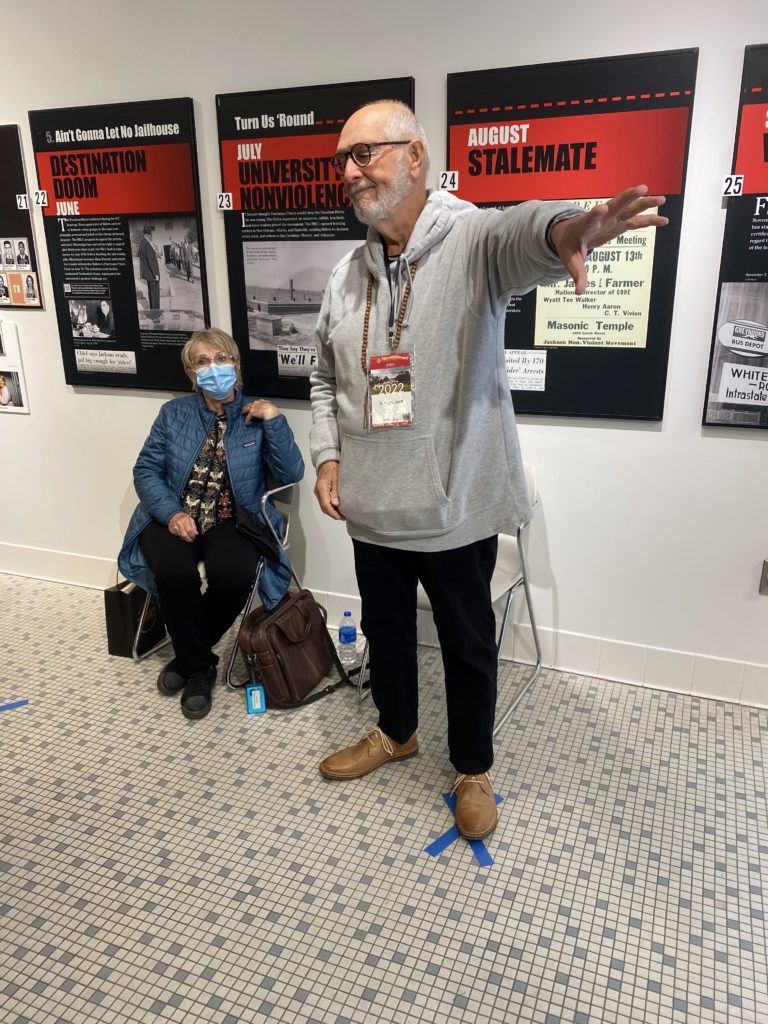

We visited the site of the old Montgomery Greyhound station, now the Freedom Rides Museum, with one of these resilient civil rights activists, Bob Zellner. The son and grandson of Ku Klux Klan members, Bob repudiated the racism of his extended family and became the first white field secretary of SNCC. During his time in the movement he helped train hundreds of nonviolent protesters and organized numerous sit-ins and marches. He cried raw tears as he recounted watching activists being battered mercilessly by a mob outside the Montgomery Greyhound station 61 years ago.

Bob pointing out the window of the Freedom Rides Museum to where the mob attacked.

We sat with Bernard Lafayette Jr., cofounder of SNCC and longtime civil rights organizer. At age 22 he assumed directorship of the Alabama Voter Registration campaign in Selma Alabama, a town where less than 1% of the 15,000 black residents were allowed to vote. Over years of organizing, he transformed Selma from a place no other organizer would touch (“The white people are too mean and the Black people are too scared”) into the nexus of the voting rights movement. The Selma to Montgomery March he helped organize would become the catalyst for the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

We listened to Valda Harris Montgomery, a civil rights activist that grew up next to MLK. Her family’s home served as a safe house and meeting place for civil rights fighters throughout the movement. When John Lewis and other freedom riders were brutally attacked in Montgomery, they sought refuge with her family. She recalled the multiple homes on her block that were bombed by white terrorists.

At the end of our time with them, Valda, Bernard, and Bob made it clear: the work was not over; the gains they had made were being lost to white supremacy and right-wing extremism today. Nothing will change without movement, they told us.

Bob front left; Valda front, third from left; Bernard front, second from right

We continued to meet people whose work demonstrated they held this same maxim in their bones: keep moving forward.

People like Michael Quess, a poet and activist working to take down statues that idolize white supremacy and slave owners. He and his colleagues at Take Em Down Nola worked to remove the statue of Robert E. Lee from its former New Orleans pedestal, and they won’t stop until they eradicate or rename the 100+ white supremacy streets, buildings, and statues in the city.

People like Burnell Cotlon, who after watching his neighborhood in the Lower 9th Ward be destroyed by hurricane Katrina, kept open the only grocery store around, operating at a loss as he rebuilt the building by hand, draining his life savings just to make sure his neighbors had food and water.

Burnell points to the place where the levees broke, less than a mile from his grocery store

People like Brandan “BMIKE” Odums, a New Orleans-based artist, whose acclaimed artwork explores Black resistance and joy.

By the work of these activists and the many more before them, gains have undoubtedly been made in America’s struggle to rid itself of a racist cancer; yet, we would be deluded to believe the work is finished. In 1968, the average Black family had roughly 9% the wealth as the average white family. Today, that gap remains stubbornly the same (source). Today, just 4 out of the Fortune 500 companies have a Black CEO. Today, Black people are imprisoned at 5x the rate of white people (source). Today, 18% of federal prisoners – 70% of whom are non-white – are employed by for-profit companies (source). Today, over 6 million Black men and women cannot vote due to felony disenfranchisement (source).

White supremacy is etched into the foundations of this country. I’ve seen it: carved into stone at the base of the 80-foot confederate monument on the Alabama state capitol, right outside the governor’s office, are the words, “The knightliest of the knightly race who since the days of old, have kept the lamp of chivalry alight in the hearts of gold.” Pulling out these hateful beliefs from their roots is the task of our generation.

If we don’t understand our past, if we warp the history of this country, we cannot see the patterns in our behaviors nor their effects. The moral arc of the universe bends toward justice, but only if we pull on it. No matter your color, we are all tied to this struggle, because as the great civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hammer once said, “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.”

Our class outside a mural painted by Brandon “BMIKE” Owens.

Let’s keep moving forward. Bryan Stevenson, the death row lawyer and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and the Legacy Museum – all sites that we visited – suggests four ways to create change:

- Get proximate to those who are suffering

- Challenge and change existing narratives

- Stay hopeful

- Be willing to do things that are inconvenient and uncomfortable

You can view his work at https://eji.org/about/

Lastly, a massive thank you to Felicia Ishino and Nathan Bean of Sankofa Impact, Professor Ed deHaan, Jay Patacsil, Cameron Boyd, and Norah Fisher for putting together such an impactful trip.

Read participants Rebecca Ballweg and Sasha Duchin‘s reflections.