Sky’s the Limit

Master developer Martin Selig has shaped the modern Seattle skyline in his own inimitable style

Some hailed the plan as bold. Others found it mad.

But Martin Selig (BA 1959) never minded the critics, even as he set out to erect the world’s sixth-tallest skyscraper in downtown Seattle.

It was the dawn of the 1980s. Starbucks was a local coffee house, Microsoft a nerdy startup and Amazon just a river in South America. Seattle, to the many unacquainted, was still a little-known dot on the far upper left of the map; a misty, mysterious land of evergreens and airplanes, salmon and a sci-fi tower straight out of The Jetsons.

Selig aimed to change that perception. An astute developer of commercial real estate across the city’s midsection, he could see where Seattle was headed, the waves of innovation and economic growth to come.

Its skyline needed a statement of intent.

And he was all in. Selig put up many of his existing properties as collateral on a $205 million loan—the largest in state history at the time—without a single major tenant committed. He painstakingly bought up an entire city block sloping between Fourth and Fifth Avenues, and bartered retail space and public amenities for added height.

After more than five years in development and construction, the Columbia Center topped out just shy of 1,000 feet (as high as the FAA would allow)—76 stories of steel and sleek black glass encasing 1.5 million square feet of elegant office space designed for 6,000 businesses.

He built it, all right. And they came.

Of course, Martin Selig’s role in Seattle’s emergence as an economic capital neither begins nor ends with the Columbia Center. Today, his signature is written across the city’s skyline. But this mid-career act of vision and tenacity, this corporate counterpart to Seattle’s earlier, quirkier landmark, certainly fired the engine.

“My philosophy was that the Space Needle told people where Seattle was,” Selig says. “The Columbia Center told people that Seattle had arrived.”

Exodus

An arrival just as momentous, in a more personal way, occurred one crystalline autumn day some 45 years earlier.

Martin Selig was born in 1936, the second child of Manfred and Laura Selig. The Seligs lived in the Bavarian hamlet of Arnstein, above the small department store they owned. One day in 1939, a neighbor tipped off Manfred that the Nazi Party had labeled the family “undesirables” and planned to confiscate their home and business.

They fled that night, hiding in warehouse basements near Frankfurt until Manfred could arrange for safe passage out of Germany. As the Second World War broke out all around them, the Seligs made their way east into Poland. Hitler’s invasion was already underway. “I can still hear the bombing of Warsaw in my ears,” Selig says.

His family eventually reached Moscow, where they boarded the Trans-Siberian Railway and traveled nearly 6,000 miles to its terminus in Korea, then hopped a boat to Japan. A steerage berth on the steamer Hikawa Maru delivered them across the Pacific, bound for San Francisco. On October 14, 1940, the ship made an unplanned stop in Seattle. “It was one of those bright, sunny fall days,” recalls Selig. “The mountains were out and the weather was beautiful. My father said, ‘We’re getting off here.’ And the rest is history.”

They arrived with nothing but the clothes on their backs and a few gold coins stashed in the heels of Manfred’s shoes. But it was a new start in a land of peace, possibility and, they hoped, prosperity.

Career change

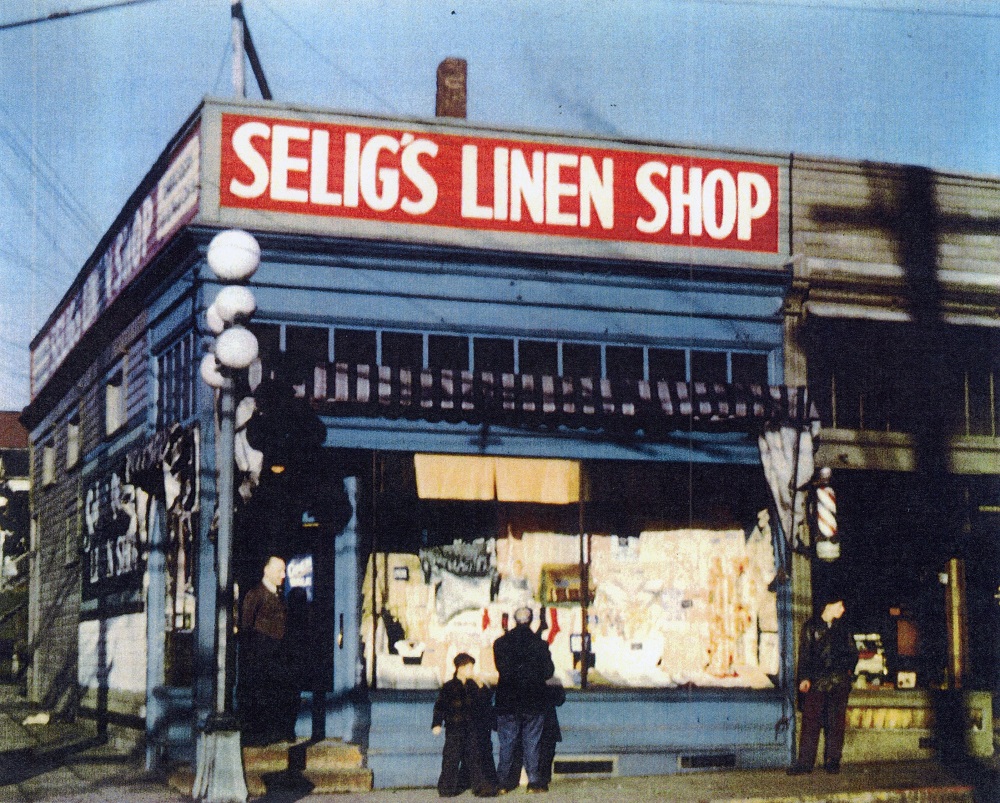

Manfred and Laura rebooted their livelihood selling textiles door-to-door, before opening a store at 23rd and Jackson. The post-war baby boom sparked a wise migration to children’s wear.

Naturally, Martin worked in the family store from early childhood to his days at the University of Washington. “At first, I’d stand on a shelf so that I could see over the counter,” he says.

He got his first taste of the real estate industry while studying business administration at the UW. In the summer before his senior year, he dated a young woman whose father was an investor of some distinction. “He would brag that he could make the stocks go up or down based on whether he bought or sold,” Selig says. “I thought, why should I let people like him control my destiny?”

When he returned to campus in the fall of 1958, Selig gathered his savings from years working in the family shop—$2,000—and made a down payment on a commercial property near what is now University Village. “I liked to show the guys in my fraternity house: that’s mine. I own it,” he says. “Sounds kind of naïve, doesn’t it? But I knew I had a good tenant who paid rent, and I knew how long it would take to pay off my investment.”

But a career in real estate? “I was in children’s wear,” he says. “That was the family business. That was what I was going to do.”

Until… “I figured out that the numbers in real estate were a lot different than the numbers in children’s wear,” he says with a chuckle. “A lot more fun.”

Around a stint in the Army and an MBA from the Wharton School, Selig sold his first property and reinvested the proceeds in the purchase of a small shopping center. Then he sold the shopping center at a profit and bought another. And so on. “Eventually I thought, why should I keep on buying shopping centers?” Selig says. “So I went and built them.”

He developed retail centers in Everett, Renton, Bellevue, Monroe and North Seattle.

Reshaping the city

In 1969, Martin Selig Real Estate began developing professional spaces, constructing its first office building in the Lower Queen Anne neighborhood of Seattle. This kicked off an incredibly productive period that saw Selig put up a new building, on average, each year for nearly two decades. These were mostly high-end high rises, stretching from Queen Anne to Belltown to Downtown, including several blocks of Fourth and Fifth Avenues in the city core.

But nothing approached the scale of the Columbia Center. This triple-tiered pinnacle of the Seattle cityscape opened its many doors in 1985 and was fully occupied within a couple of years.

By then, Selig owned more than one-third of Seattle’s downtown office space. A 1986 article in the New York Times proclaimed that he had done “more to change Seattle’s skyline than anything since the Great Fire of 1889.”

In 1989, Selig made the uncharacteristic decision to sell the Columbia Center, for $354 million. “It was a lot of fun, but also all-encompassing,” he says. “When I sold it, it felt as if the shackles had come off.”

Free once more to pursue new projects, he continued developing commercial buildings across the city and the years. Today, Martin Selig Real Estate owns more than five million square feet of office space—99-percent occupied—with another 1.75 million in development.

Secrets to success

It’s not by accident that Selig has built a real estate empire through so many of Seattle’s heaving cycles of boom and bust. His secrets to success are hardly secrets at all.

He has rarely sold properties, compounding on the upward trend of Seattle’s real estate valuations. He has maintained a lean, independent organization that fully taps the talent of its tight-knit team of loyal colleagues. And his strategy has remained remarkably consistent. “I give Martin a great deal of credit for being disciplined,” says longtime consultant and friend Jack Rodman. “A great deal of his success comes from knowing his market, knowing what he does well, and doing it well. He has never drifted.”

That’s not to say he hasn’t evolved. Rodman adds that Selig has transitioned his developments from serving the traditional office needs of accountants, lawyers and insurance brokers to meeting the demands of a new generation of entrepreneurs and tech firms seeking flexible work environments and one-of-a-kind architecture.

And then there are the intangibles. Those who work closely with Selig describe him with words like determination, tenacity, courage, vision, innovation and optimism.

His youngest daughter, Jordan, the organization’s executive vice president, counts a long list of indelible lessons learned from her father: “Do not miss the forest for the trees. Never burn bridges. Always view the glass as half full. Listen more than you speak. Think outside the box. Never sell. And, above all, follow your passion.”

Art + architecture

Selig is certainly a man of many passions.

In addition to his absolute dedication to the business, he also is a devoted patron of the arts and an accomplished artist in his own right. Though he describes himself as a “dabbler,” his vivid abstract paintings fetch thousands of dollars at charity auctions. His buildings are de facto galleries of fine frescoes, murals and sculptures by renowned artists (including the eye-catching giant “Red Popsicle” outside of Fourth & Blanchard, created in 2013 by his wife, the artist Catherine Mayer).

Now in his early 80s, Selig continues to play as hard as he works. An avid skier, he managed 27 days on the slopes last winter (“If I’m lucky,” he says, “I’ll get 50 this year”). And while most of his fellow motorcycle-riding “Hell’s Rotarians” have long since retired, he still gets out on his Harley-Davidson Softail as often as he can, touring exotic locales with friends each summer.

“Martin is a Renaissance man,” says Rodman. “I might start calling him Leonardo.”

What’s next?

Selig’s longevity has certainly surpassed the great Italian master, who took his last commission at age 64. “I think Martin is accelerating, in a way,” says Erik Mott, design principal with the architecture firm Perkins + Will. “He keeps moving forward, keeps innovating. He believes in his ability to deliver projects that others might shy away from.”

Ask Selig for his favorite, and he’ll inevitably reply: “The one we’re working on now.”

There are plenty:

-

A gleaming high-rise is growing out of the historic Firestone Building in South Lake Union.

The recently completed 15th and Market is Selig’s first foray into Ballard.

- 3031 Western will be his first luxury residential high rise, with commanding views, a green roof and solar shading.

- Third and Lenora, a 36-story tower, will be WeWork’s first “WeLive” residential/commercial concept on the West Coast.

- 400 Westlake, Selig’s South Lake Union debut, will modernize and expand the 1929 art deco Firestone Building to create the greenest office structure of its size in the world.

- The historic 1950 Federal Reserve Bank (1015 Second Avenue) will be restored—including its massive vault doors—and repurposed as a modern office building, topped by seven additional floors sheathed in glass.

- The former Commuter Building (800 Alaskan) will be reborn as an 17-floor mixed-use building—office, residential and retail—fronting the Seattle waterfront now that the viaduct is coming down.

Selig’s first luxury residential high rise will offer green features and commanding views of the Puget Sound.

So, Selig has his work cut out for him. And he predicts that Seattle’s current transformation will offer considerable opportunities for some time to come. Not that he’s contemplating retirement. “I haven’t started working yet, so how could I retire?” he says. “This continues to be a challenging, extremely creative outlet—and a lot of fun.”

American doer

Selig has led a remarkable life, from escaping Nazi Germany to remaking the skyline of the city that took him in so many years ago.

“Martin embodies what I would call the great American story, a rags-to-riches success,” says his friend Jack Rodman.

But Selig’s American story is a tale of doing rather than dreaming. “You know, it just happens as life goes on,” he says. “You’re living in the dream.”

Besides, he’s too busy to dwell on the past for long. There’s always that next run, next ride, next canvas, next building awaiting.

“I look forward. I don’t look back,” he says with a wry smile. “You can’t drive a car forward looking at the rear-view mirror.”