Trend Spotting

In Washington and around the world, Dan Baty sees—and seizes—business opportunities ahead of the curve

Dan Baty

“Not sure how you’re going to start this story,” says Dan Baty (BA 1965), with mischief in his eyes.

Baty, the founder and chairman of the private equity firm Columbia Pacific Management, and longtime colleagues Rick Evans (MBA 1971) and Matt Powell (BA 1993) have just regaled me with a thousand-and-one tales of entrepreneurial daring in Asia and beyond. Of scouting a hospital site in a Sumatran jungle. Of developing a clinic on the vacant frontier of Bangalore. Of introducing the egalitarian principles of Western healthcare to the region’s rigid social hierarchies. Of navigating China’s byzantine bureaucracy to serve the seniors of Shanghai and Beijing. Of reading the tea leaves—and refrigerator sales. Of seeking stability in Africa. Of transforming a local wine-making hobby into an industry. Of getting into wealth management by popular demand.

Where to begin, indeed.

“The center of your story should be Dan,” advises Evans, who has worked with Baty for nearly five decades.

“But you can’t use my name,” Baty deadpans.

He’s joking… I think.

Finally, a wry grin confirms it.

“We keep a pretty low profile here,” he says, laughing.

That’s an understatement of understatement. With deliberately little fanfare, Baty & Co. have built the most successful—most fascinating—Seattle company you’ve never heard of. Even the headquarters of Columbia Pacific, a modest five-story office complex overlooking Seattle’s Lake Union, is camouflaged by the insignia of former occupant Hart Crowser.

Baty has more important concerns. More interesting concerns.

Columbia Pacific is the first and foremost foreign player in healthcare across Southeast Asia and India. It’s the only foreign-owned senior care provider in China. It runs the largest family-owned winery in Washington state. And its financial advisory wing, Columbia Pacific Advisors, has more than $2 billion under management.

Of course, Baty would tell you that the secret of his sustained success is assembling and empowering a great team—which happens to be richly powered by fellow grads of the UW Foster School of Business. But ask any of them and they’ll point you right back to Baty. He’s always been the man with the plan, an investor as bold as he is visionary.

So this epic story of many chapters, spanning North America, Europe, Asia and Africa, is really his story. And it begins in Tacoma.

Early senior moment

Baty was born and raised in the “City of Destiny” on the South Sound. By age 10 he knew that he wanted to be in business, though he had no idea how that aspiration would take shape. He earned a BA in accounting at the University of Washington and a JD at Harvard Law School, and worked in the tax department at Price Waterhouse in Seattle.

Real opportunity knocked early. A man named Fred Diamond, for whom Baty had caddied as a kid, had founded a small chain of nursing homes called Hillhaven and was looking for an assistant. Baty passed. But he knew that Medicare and Medicaid had just been enacted. And he could see that America was aging. When Diamond came back with a sweetened offer to run the company, Baty jumped. “I was 26 at the time and thought, what do I have to lose?” he recalls. “This changed the whole dynamic of my career.”

Over the next 17 years, Baty built a model long-term care provider network, introducing to the industry a broad range of rehabilitative and therapeutic services. “We always said that we had to take care of the patient first,” Baty says. “If the economics suffer, they suffer.”

The economics did not suffer. At its 1979 sale to National Medical Enterprises (now Tenet Healthcare), Hillhaven was the nation’s second-largest nursing home company. When Baty finally turned over the keys in 1984, the network of 500 properties served 45,000 seniors and was doing $1 billion in annual sales.

It was time to try something new. “I was 42 years old,” he says. “And I thought, let’s find out if I’m smart enough.”

Emeritus entrepreneur

Smart move number one: establishing Columbia Pacific in 1984 as a management hub for what would become an overlapping portfolio of healthcare, senior living and other business concerns that stretches around the globe.

In 1987, Baty invested in Holiday Retirement and, as chairman, developed a pioneering network of 350 retirement communities across North America and Europe—each featuring private apartments or cottages and all-inclusive services such as meals, transportation, activities and housekeeping—before brokering a $7 billion sale to Fortress Investments in 2007.

In 1993, Baty founded Emeritus Senior Living, a provider of assisted and independent living, memory care and skilled nursing. He took Emeritus public in 1995 and, over the next 15 years, expanded its network to 47 states. Its 2014 merger with Brookdale Senior Living created the nation’s largest network of senior care and memory care in America, with more than 1,000 facilities, 80,000 employees and $5 billion in revenues.

This was healthcare at scale.

That scale was about to get bigger.

Aging Asia

Baty had known Rick Evans since high school. They both attended the UW and were brothers in the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity. But while Baty equipped himself for business, Evans studied in the Far East and Russian Institute (in what is now the Jackson School of International Studies). “I remember that I was reading Dostoevsky and Dan was reading The Financier,” recalls Evans. “I thought, we are going in different directions.”

But their paths soon converged again. Shortly after Evans completed his MBA at the UW. Baty called on his old friend to help build Hillhaven, then Holiday, then Emeritus.

Then in 1996, they hatched the idea to take their hard-earned expertise in senior health and housing to Asia. On paper, it looked an incredible opportunity: booming economies, aging populations, shifting societal and familial traditions.

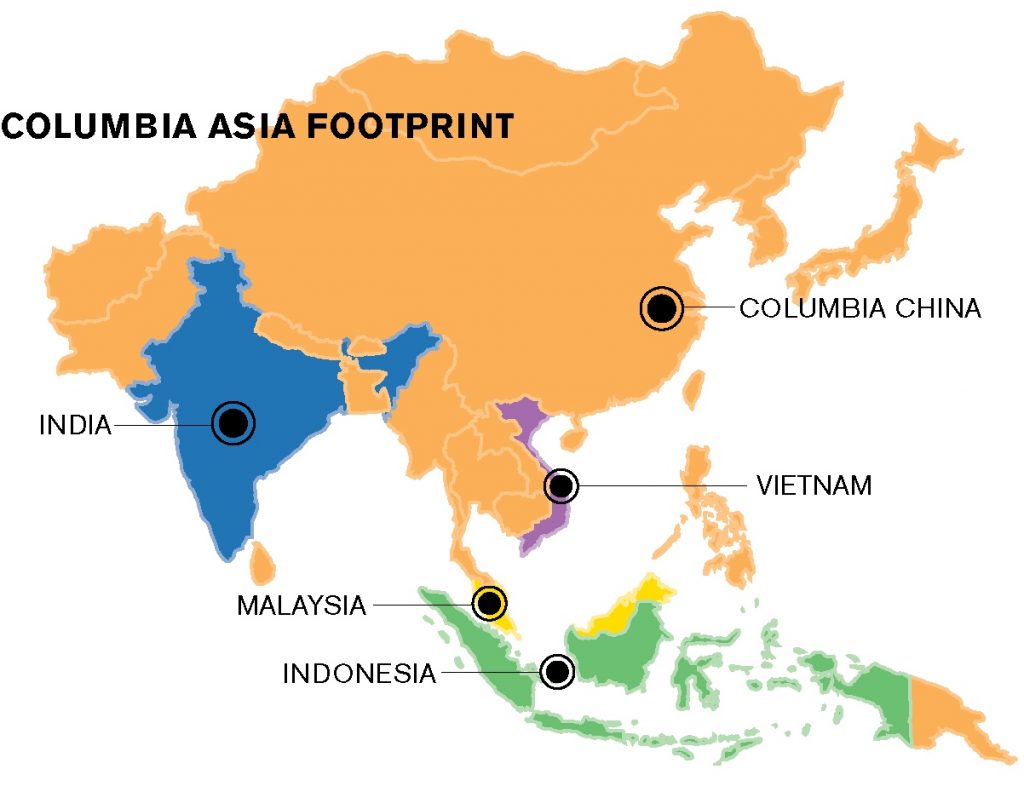

Baty and Evans formed Columbia Asia to find out just how good an opportunity. Evans, with at least an academic interest in Asia, became the company’s man in Malaysia, where he established a home and base of operations.

They chose Malaysia as a test market because its language and law are based on the familiar British system. And its economy and infrastructure were developing rapidly.

“But when we got there,” Baty says, “it became clear that we were 15 years too early.”

Plan B

Instead, they spotted a more immediate opportunity that looked equally promising: healthcare.

The region’s economic miracle was producing a fast-growing middle class, throngs of people moving from farms to cities. Among a consensus of official economic indicators, Evans latched on to what might be called the “refrigerator index.” “When you own a refrigerator, it changes your life. It means you have electricity, and no longer have to find food every day,” he explains. “You are a member of the middle class.”

At the time, refrigerator sales in Malaysia were rising at 17 percent per year.

And what else was this burgeoning bourgeoisie going to spend money on? Education and healthcare. Of the latter, the only existing options were dilapidated government hospitals or exorbitant private clinics for the rich. Yet the widening middle was living longer, and experiencing more cases of cancer, diabetes and cardiac diseases.

“Somebody’s going to build quality hospitals for the middle class somewhere in Asia,” reported Evans to Baty.

“You’re absolutely right,” he replied. “Let’s go do it.”

They started with an extended-care facility off a newly laid freeway in a burgeoning suburb of Kuala Lumpur. Extended care was easier and less expensive to introduce than a hospital. And it offered a chance to test the regulatory environment and size up the market and competition—at the time consisting largely of Indonesian maids hired to provide in-home care after hospital visits.

Columbia Asia brings state-of-the-art healthcare to the region’s burgeoning middle class.

Columbia Asia’s first state-of-the-art facility, staffed by respected physicians and nurses and delivering patient-centered care, was a hit. And, for Baty and Evans, it was a trove of insights.

Innovate, replicate

They began building similar extended care clinics followed by hospitals elsewhere in Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia and India. But their expansion was methodical, not rash. They hewed to a sensible model and made improvements across the network as they went. And they fought the urge to grow too fast in a market that seemed endless.

Around this time, Matt Powell had come to work at Emeritus before Baty and Evans talked him into moving halfway around the world to help manage healthcare development on the ground.

“It was amazing working with Dan and Rick,” says Powell, who recently took over for the retiring Evans as director of global development for Columbia Asia. “Their ability to see opportunity through all the scary and chaotic nature of some of these emerging markets is a skillset that no one else could have taught any better.”

There were no better lessons in stress management than the hospital they rebuilt in the remote rainforest metropolis of Medan, Sumatra, or the first health clinic they constructed outside of Bangalore.

They developed their first Indian property on a freeway exchange in the middle of nowhere. But Evans’ research showed that young people were moving toward the emerging tech industry, and the tech industry was moving toward the city’s outer rings. “When we bought the land, there wasn’t anything within a mile,” Baty says. “By the time we opened, there were a million people living within a stone’s throw.”

A facility designed for 300 visits a day was soon drawing 900.

This became the pattern for expansion across the subcontinent. Baty, Evans and Powell would develop a location near a new tech center and offer the only viable alternative in health care: high quality at a reasonable price (which even appealed to higher-end consumers, judging from some of the cars they found parked outside).

Secret sauce

It’s one thing to spot opportunity. But to turn opportunity into sustained success? That requires a whole different skill set, an ability to innovate operations.

Above all the issues of building a company across distinct regions of the world, Baty, Evans and Powell discovered that their real competitive advantage is in providing a superior customer experience. In each location across the region, they hired local management rather than expats. They began pairing a respected physician with an administrator from the hospitality business. Their culture of equal care for all provided a welcomed refuge from the cultural strictures of class hierarchy. And their demand for consistently ethical management and transparency in billing and compensation made Columbia Asia popular with patients, employees, even ambulance drivers—not to mention the rapidly developing health insurance industry.

And they kept quality high and costs firmly in the grasp of the rising middle class by building efficiencies across the network and limiting expensive procedures.

Having Evans and Powell living as locals in the places they did business made all the difference. “The story of investing in Asia is understanding the barriers to entry,” Evans says.

“And it can’t be done,” Baty adds, “unless you’re there.”

Time for seniors

Following a similar model, Columbia Pacific has finally entered China. “The regulatory system and risk quotient are different there,” Baty says. “But the societal issues are the same as throughout Asia. There’s an enormous emerging middle class and a healthcare system that isn’t keeping up with the demand.”

Though the government has just opened the hospital market to foreign investment, Columbia China already has facilities under development in Shanghai, Wuxi, Jiaxing and Changzhou.

Dan Baty reviews construction plan for the company’s expansion into China.

And even before hospitals were a possibility, the company was already operating in China. Through a joint venture called Cascade Healthcare, Columbia Pacific became the first foreign-owned senior care provider in the country four years ago, importing the proven Emeritus model of care and rehabilitation to seniors in Shanghai and Beijing.

The quick success has inspired Baty to revisit that original plan to introduce best-in-class residential senior care throughout Asia.

“It’s time,” he says.

Ringing endorsement

There is more, of course. Through Columbia Africa, Baty’s company is testing the waters of healthcare in Kenya. His purchase of Remote Medical International adds a mobile medical service to faraway mining and drilling operations. And the March acquisition of India’s Serene Senior Care launches new line of business developing senior housing in the region.

Zoom out from a map of the Columbia Pacific Management’s expanding network—30 healthcare facilities in operation, a dozen opening soon, and a residential senior care business just taking off—and a larger strategy becomes obvious: healthcare for the young and old of an exploding middle class in the most densely populated parcel of the world.

“We’re a significant healthcare provider for half the world’s population,” Baty says. “We don’t have to go anywhere else. The demand in these countries is going to be enormous over the next 15 years. And we’re already there.”

“We have infrastructure and a respected brand,” Powell adds. “And we’ve learned how to take advantage of them.”

They’re only getting started. In recent months, Columbia Pacific Management forged game-changing strategic partnerships with two of the world’s most influential investment firms. In July, Tokyo-based Mitsui & Co., one of the world’s largest trading companies, invested $101 million to support expansion of healthcare services through Columbia Asia and Africa.

They’re only getting started. In recent months, Columbia Pacific Management forged game-changing strategic partnerships with two of the world’s most influential investment firms. In July, Tokyo-based Mitsui & Co., one of the world’s largest trading companies, invested $101 million to support expansion of healthcare services through Columbia Asia and Africa.

“Talk about a calling card in Asia—or the world,” Baty says. “The Mitsui connection is significant.”

In October, Singapore-based Temasek Holdings weighed in with a $250 million investment in Columbia China’s growth.

They have the money, the model and a market that is calling their name.

“Local governments are aggressively hustling us to come there,” Baty says. “They all want an international-standard hospital in their market to attract other foreign investment.”

What’s next

Columbia Pacific Management, after so many years, may no longer be the best-kept-secret in Seattle business. Baty takes stock of this development with characteristic quiet satisfaction.

“You don’t get that many opportunities—particularly when you’re not science or tech-oriented—to really make a difference,” he says. “And I think we have made a difference, both in providing quality healthcare and in creating unique opportunities for young people.”

It’s that talented operational team, after all, that liberates Baty to focus on what really sparks his passion: the intellectual challenge of seeing—and seizing—new business opportunities.

“I don’t really run anything,” he admits. “I mean, I’m responsible for how things run. But what I get paid for is knowing what’s going to happen five years from now.”

And nobody does it better.

From hobby to industry

Dan Baty (BA 1965) says that the best word to describe how he got into the wine business is “foolishly.”

A group of University of Washington professors had been making wine in the garage of the dean of Arts & Sciences, then loading it into a station wagon each Saturday to deliver to the University Village QFC for sale to the public under the label Associated Vintners. When they outgrew the garage in the 1970s, the state’s proto-vintners asked Baty to help finance and manage the expansion. “I knew nothing about wine,” he recalls. “But I liked the people.”

It didn’t take a genius to see the lack of shelf appeal in a bottle of Associated Vintners. So Baty acquired the struggling Columbia Winery in 1980, just as Washington’s viniculture industry was about to go global. He grew Columbia into one of the state’s largest before selling the company but retaining the land and, most importantly, the water rights.

In 2003, the Baty family founded Precept Wine, a portfolio of fine local wines that has become the largest privately owned in the region.

His favorite? Alder Ridge Cabernet, produced from grapes grown on 900 acres of sumptuous vineyards that roll down to the mighty Columbia River.

“But I really don’t know that much about wine and how it’s made,” Baty admits. “I know the business of wine, which is a different thing from most people who own wineries in the state.”

“I’m from Tacoma,” he adds, laughing. “I drink beer.”

What’s your favorite place in Asia?

“Vietnam,” says Dan Baty. “For a communist country, it’s the most capitalistic place in the world. By that I mean the people and the culture. Everybody’s hustling to make money.”

“While we were there they passed a law allowing for private businesses, provided they didn’t employ more than 12 people. Within a year, there were 400,000 of them,” Rick Evans adds. “I mentioned to a very old Vietnamese man I got to know that this was amazing. He said, ‘Oh Rick, capitalism is older than the hills of Asia.’ ”

How’d a healthcare company get into wealth management?

“We began managing part of the family’s investments and realized we were doing just as well as the professionals,” says Dan Baty. “Since we had made a lot of money for investors in Seattle and Tacoma over the years, many of them asked if we’d just keep doing it. All of a sudden we’re in the wealth management business with Columbia Pacific Advisors. We don’t advertise. We don’t promote. People just started calling us.”

What’s your advice for students?

“Take philosophy and all the accounting you can get,” says Dan Baty. “I don’t mean that specifically, but the point is that you should learn how to think and add at the same time.”